Every child who had to be dragged from the sea, screaming wild, howling for entry, wonders what it would be like if they’d broken free from their parents’ grasp, run back to the surf, and traded their limbs for fins.

“Sea Blast” is a baroque, embroidered sea-poem. Sargasso has stitched it. There are no embankments against tide and time here: not human passion, not iron, no industry of man’s desire or man’s jealousy or man’s architecture. Nothing keeps the sea, embodied as a mad island woman, from surveying and claiming what she wants. Including what she’s wed.

Gilberte O’Sullivan gathers starfish-splayed images, unites them into a coral reef of beauty and foreboding: “little fish scholars”; “scrolls of perishable ideas”; “the sign of the mast”. In the domestic disharmony of pirate husband and maritime wife, in the slow and insidious untethering of the former’s defenses against the latter, the poet both builds her caverns under the ocean, then chips at them, worrying language to prise out pulsing miniature snakes of malaise. What a fine, sanguineous festering O’Sullivan invokes.

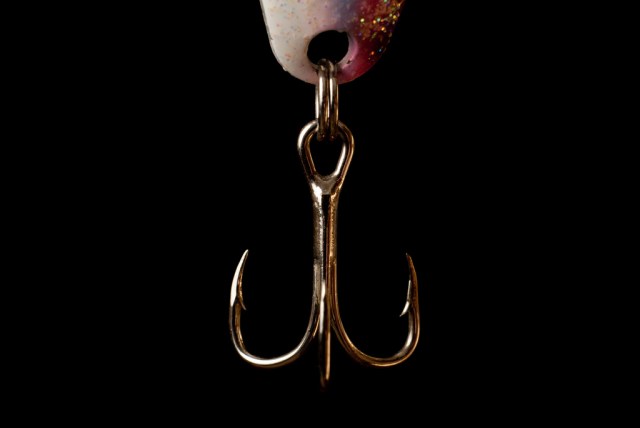

The poet needles gentleness out of the poem with sharp, underwater spears, leaving us with the long, vicious effects of saltwater-erosion. The sea takes everything when you aren’t looking: time, love, decency, family ties, even a bowl to cast your cares into, weeping. Yet it is the very cruelty of the poem that sings us the most sublime of narratives: an anti-conquest fable, like something out of a waterlogged tome, promising a vengeful end of any man who wants to marry a woman into submission without her tacit seal of approval.

What a chorus of oceanic comeuppances is “Sea Blast”. What an augur of inevitability. What a promise, waiting to rise up and eat everything you own, with salt. Dive in; forget drowning.

Read “Sea Blast” here.

Gilberte O’Sullivan was a featured writer in “Who’s Next” at the 2014 NGC Bocas Lit Fest, and was again featured at the festival in 2017’s “Stand and Deliver”.

This is the eleventh installment of Puncheon and Vetiver, a Caribbean Poetry Codex created to address vacancies of attention, focus and close reading for/of work written by living Caribbean poets, resident in the region and diaspora. During April, which is recognized as ‘National’ Poetry Month, each installment will dialogue with a single Caribbean poem, available to read online. NaPoWriMo encourages the writing of a poem for each day of April. In answering, parallel discourse, Puncheon and Vetiver seeks to honour the verse we Caribbean people make, to herald its visibility, to read our poems, and read them, and say ‘more’.

This is the eleventh installment of Puncheon and Vetiver, a Caribbean Poetry Codex created to address vacancies of attention, focus and close reading for/of work written by living Caribbean poets, resident in the region and diaspora. During April, which is recognized as ‘National’ Poetry Month, each installment will dialogue with a single Caribbean poem, available to read online. NaPoWriMo encourages the writing of a poem for each day of April. In answering, parallel discourse, Puncheon and Vetiver seeks to honour the verse we Caribbean people make, to herald its visibility, to read our poems, and read them, and say ‘more’.