Published in 2008. This Edition: Vintage Books, 2011.

Matt King’s life, all things considered, could do with a major overhaul. His wife, Joanie, has been in a coma for twenty-three days, courtesy of a boat-racing accident. Matt finds himself flounderingly out of depth in the management of his two daughters: rebellious, drug-recovering Alex, and exuberant, highly peer-pressurized Scottie. Lurking in the background of this familial implosion is the weight of a decision Matt must make: as principal trustee to a collective of Hawaii’s wealthy, royalty-descended landowners, he must say to which highest bidder huge tracts of heritage land should be sold. As time ticks by, and Joanie’s future prospects look increasingly grim, Alex stuns Matt with the revelation that Joanie has been unfaithful to him for some time. Bundling up his daughters, Matt takes them on an unexpected trip to locate the man Joanie possibly loves more than him, so he, too, can pronounce final farewells at her bedside.

Matt King’s life, all things considered, could do with a major overhaul. His wife, Joanie, has been in a coma for twenty-three days, courtesy of a boat-racing accident. Matt finds himself flounderingly out of depth in the management of his two daughters: rebellious, drug-recovering Alex, and exuberant, highly peer-pressurized Scottie. Lurking in the background of this familial implosion is the weight of a decision Matt must make: as principal trustee to a collective of Hawaii’s wealthy, royalty-descended landowners, he must say to which highest bidder huge tracts of heritage land should be sold. As time ticks by, and Joanie’s future prospects look increasingly grim, Alex stuns Matt with the revelation that Joanie has been unfaithful to him for some time. Bundling up his daughters, Matt takes them on an unexpected trip to locate the man Joanie possibly loves more than him, so he, too, can pronounce final farewells at her bedside.

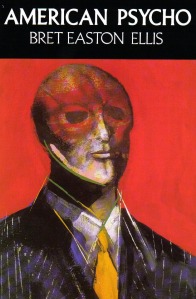

It isn’t hard to fathom the reasons why this novel inspired a touching, thoughtful film adaptation. (As you can see, the book’s cover features a haunted George Clooney gazing into the distance, perched on Hawaiian littoral, flanked by sandcastles.) This is one of those books that reads as though there’s a script already imbedded in the prose, waiting to be lifted, licensed and imaged for the screen. Almost every good point I can make about the visual imagery of the descriptions tie in to how stunningly well they salute the mind’s eye. Witness, for instance, this picture of Scottie, who, having gone on an impromptu mini-adventure with her father to Alex’s boarding school, arrives decidedly the worse for wear.

“Scottie looks thrilled by the situation. Her red sores are bright in the hall’s fluorescent light. Her T-shirt says VOTE FOR PEDRO, whatever that means, and her hair is sticking up in places and matted down in others. In one section near her ear, the hair is held together by some unknown substance. She had fruit punch on the plane, and her lips and chin are stained the colour of raw meat.”

The images Hemmings conjures are consistently entertaining, moulded and primed for dark, honest humour, as well as aching sadness. The most notable include impressions of Matt’s difficult, likeable daughters, but also of Matt himself, and the way he perceives everyone and everything around him — tourists; his daughters’ cohorts; hospital staff; the ways in which other people perceive him; his fellow landowning descendants; the shifting structures of Hawaiian landscapes. Matt is a faithful archivist of the place he’s from, the place he loves, and his daily photobooks of observation afford rich, deeply funny insights into a place typically thought of in terms of multicoloured leis and roasted pig cookouts on pristine beachfront.

We think of the impossible caverns of love and grief as thorny terrain to demystify, and perhaps some of the best fiction shies away from putting such things into quantifiable, qualifiable terms. The opposite approach is explored in these pages, with Matt the compass for one man’s perambulations through the messy business of re-evaluating one’s love while simultaneously preparing for the worst. This isn’t to suggest that our protagonist is the only person in the novel whose experiences aren’t linear. Conversely, Matt’s interactions with his daughters, with his in-laws, with Alex’s sort-of-but-not-really boyfriend, Sid, all work like character references in a stuffed docket for emotional complexity. No one loves in singular colours; no one tolerates loss on a full palate of either beatitudes or vices. In one of my favourite passages of the novel, Matt reflects on a rare, treasured memory: his perpetually self-sufficient wife seeking comfort in his arms, immediately following a harrowing trauma.

“She sank down to the rocks, pulling me down with her, and then she lunged into my chest and wept. We were in the most awkward position on those rocks, but I remember not being able to move, as though the slightest movement might upset either her or the moment. Even though she was sobbing in my arms, it was a nice moment for me, to be stronger than her, to be needed by her, and to see her so fragile.”

The torment truly sinks in when Matt contemplates, right on the heels of this, the excruciating possibility that Joanie has dismantled her armour thusly for the man of her affair, too… and, most damning of all, there’s no reliable way of confronting either of them. Matt, like so many people stricken with the dead weight of an infidelity involving two silent sources, is saddled with a lifetime’s worth of maddening, perhaps debilitating hypotheticals.

Immersing yourself in Matt’s bleak and blackly comic inner monologues is as thrilling as it is because it grants you the relief of uncensored permission: to feel fully all those ideas that aren’t politically correct, to hate your children and love them; to hate your wife and love her; to want to be the best person and the worst all bound up in one festering, grinning knot of humanness.

Reading The Descendants is a shotgun ride in the author’s dodgy pickup truck, skirting some emotional landmines, rattling full-on into others. This, really, is what I love best about the novel: it confronts the non-poetic shit storm that reality quite often resembles, without any fumblings towards a sense of… literary rightness. There aren’t any perfect similes for pain, or, if there are, Hemmings doesn’t concern herself with trying to unearth them for our benefit. Truly, cosmically horrific things are as likely to happen to you as they are to the person alongside you in the bus.

How you feel about this book will depend largely, I think, on whether or not you require, or secretly long for, a primer on how to navigate life successfully, with minor bruising. If you find it hard to fathom that there can be one good way to be a worthy father, lover, landowner, descendant, or decent human being, then you’ll be hard-pressed to read something more organically attuned to the general state of loving, grieving and every curious, maddening human state from here to there.

I pledged to give away all the books I bought myself in 2012. I’m giving this book to my exuberant and all-round excellent friend and fellow writer, Leshanta, whose work I’ll be featuring at Novel Niche in a future coming to you shortly.

Published in 2011 by

Published in 2011 by