First, there were beasts. Second, we learned to breathe through them. This is how you imagine any feral transaction was initiated: your ancestress, and the snarling familiar she called to her side. You imagine it took place in sunlight-dappled glens; over the thin sheet of ice trapping the lake vastness beneath; in the full moon of pioneering blood, and the monsoon fever of a final kill.

Surely it wasn’t meant to be this way, you think now as you reluctantly loop your retriever’s leash to a signpost of all the human places he is forbidden access. Surely, there was a way to walk in more truthful wilderness.

Jessamyn Smyth’s new collection of fictions knows wilderness and human ruin. The Inugami Mochi takes its title from a Japanese folkloric family — one part fur, the other flesh. A bond in which the beast — the dog-god, inugami — functions as stalwart spiritual and territorial defender to her human, inugami mochi are frequently ill-perceived by more civilian members of society. So it is with Cecily and Dog, the partnership whose interlacing, overlapping stories together form the spine of the work.

Of spines, the textual alignment of these stories are set, or broken, to let the light of anguish in. Smyth arranges her texts with the anatomical composition of a body uncovering, systematically, its own portrait of ruin. The more Cecily — a strident, opinionated literature teacher who favours Dog’s company above all others, grimacing at the soulless social gatherings she forces herself to attend — and Dog cleave to each other, the more mortal instruments of pain try to vivisect their united landscape. The author’s attention to catastrophe resulting in trauma and the resultant slow crawl of rehabilitation is a scrying bowl into which many of the stories dip for focus, and for revelation.

Sometimes the grievances can be cured by water, as a bath with Dog in the tub cleanses him of a decaying deer carcass’ yellow and green putrefaction, in the collection’s opening story, “A More Perfect Union.” In “Bears”, water is the medium through which carnage flows, as Cecily suffers a brutal bisecting blow, splitting skin as bear and woman wrestle in a swimming pool for supremacy and survival. Whether this happens literally pales in significance to Smyth’s devotion to litmus-testing the body’s dependency on, and terrorized relationship with, its own unexpected strengths.

At the microstructural level, Smyth’s lines are conjured to both devastate beautifully and rout any sickness of complacency from the text. Cecily and Dog cavort, roam and contrive together in natural beauty; far removed from malls and marketplaces, they trade unanimously in the soulful commerce of each other. The author surrounds us in the resplendence of the unbuilt world, never undermining its fragility and propensity for cruel acts. It is nature, empyrean and indifferent, that deals Dog a critical hand in the collection’s titular story. “The Inugami Mochi” draws the reader in totemically, harnessing all the sudden assault of an unexpected torturer’s song, splitting the silence. It rests in the collection with gravid unease, and in the very microstructure of its telling, Smyth eschews ornamentation for the finer poetry of desperation, dragging us and Dog in the throes of

“crying, and crying, and lifting, and holding him shut, and scraping them both up the impossible section, and then they are past it and she gathers him in again and holds his wound shut and again begins to run, close to the road now, a final series of hills, her arms and legs and lungs and spine flaming, his weight somehow more dense now even than it was, and the denseness terrifies her,”

And we, reading, are dismantled on a cellular level, which is as it should be. The stations of devastation in The Inugami Mochi intend no less than this raw, throat-rasping genuflection.

Smyth’s stories are more mirthful than this baleful tussling with nature, water and blood suggests — indeed, some of its bloodiest segments, such as the impishly-named “Copper T”, prance giddily into topics threaded with gore and gristle. An intrauterine device installation sees Cecily “doubled over and hemorrhaging into a pad the size of Manhattan,” and she devises uproarious titles for the misadventures of her vagina in both contraception and canoodling. Leavening wry humour with sharp self-cognizance, Cecily guards her wounds close:

“At no time was she unaware of the metal passenger in her body: its shape and position, its bright, sharp gleam.”

We navigate life strewn on the inside with metal passengers. The Inugami Mochi reminds us that we’ve stranger, even more durable relics buried within us — none so potent, so belly-to-spine embracing, as dog’s tooth and hound hearkening. Dog, in all his devotion, his canny prescience, his love of water and the throwing heat of his love: all this will make you not only adore him, but reach for the wilderness within your breast that you’ve been forsaking.

Necessary, pointillist-studded with grace, ferocity and loss, The Inugami Mochi will bid you rip the metal out, replace it with something that barks and bolts and bleeds.

Jessamyn Smyth’s The Inugami Mochi will be released on February 15th, 2016. For more information and preorder links, visit the official publisher’s page at Saddle Road Press.

Twenty four years have elapsed since the July 1990 attempted coup by the Jamaat al Muslimeen. Those who recollect the events of those six days in Trinidad and Tobago’s history do so with collective unease, channeling repressed fury and a kind of malaise that’s difficult to translate into common speech. This is what Monique Roffey’s fourth novel, House of Ashes (

Twenty four years have elapsed since the July 1990 attempted coup by the Jamaat al Muslimeen. Those who recollect the events of those six days in Trinidad and Tobago’s history do so with collective unease, channeling repressed fury and a kind of malaise that’s difficult to translate into common speech. This is what Monique Roffey’s fourth novel, House of Ashes (

Published by

Published by

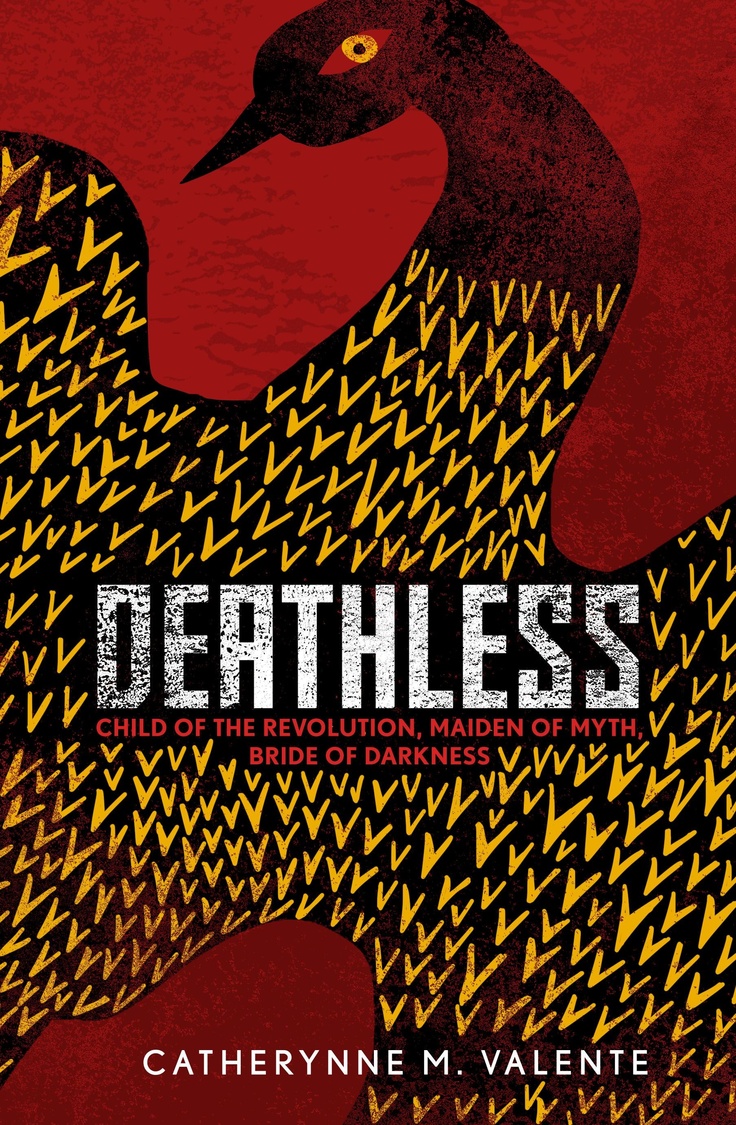

There are various iterations of his accursed name, but in Slavic folklore, Koschei the Deathless augurs ill, particularly for the beautiful, chaste maidens he lures into his lap. As the ancient stories have it, Marya Morevna is his opposite: a steel-tempered warrior woman who brings the immortal, undying Tsar to heel, with chains and with stratagems. Russian children cut their teeth on these parables, and in their imaginations, such figures are hewn from the stardust of reality, fashioned in the space where our inherited stories possess, in their childhood telling, the greatest strength.

There are various iterations of his accursed name, but in Slavic folklore, Koschei the Deathless augurs ill, particularly for the beautiful, chaste maidens he lures into his lap. As the ancient stories have it, Marya Morevna is his opposite: a steel-tempered warrior woman who brings the immortal, undying Tsar to heel, with chains and with stratagems. Russian children cut their teeth on these parables, and in their imaginations, such figures are hewn from the stardust of reality, fashioned in the space where our inherited stories possess, in their childhood telling, the greatest strength.

I feel compelled to share with you that my hands are shaking, a little, as I write this down. Reading books like these pry at the elusive answer to the unspoken question of how deeply an experience, literary or otherwise, can mark us, until we begin to chafe gracelessly against the semaphore of its instruction.

I feel compelled to share with you that my hands are shaking, a little, as I write this down. Reading books like these pry at the elusive answer to the unspoken question of how deeply an experience, literary or otherwise, can mark us, until we begin to chafe gracelessly against the semaphore of its instruction. First published in 1977. This edition: 2012,

First published in 1977. This edition: 2012,

Published in 2012 by

Published in 2012 by  Published by in 2012 by

Published by in 2012 by

Published in 1999 by

Published in 1999 by