Published by Del Rey in 2013.

Published by Del Rey in 2013.

Would you care for a bit of inter-species, mixed faction romantic mingling, housed in a travelogue-formatted space odyssey? That’s at least some of what Barbadian writer Karen Lord is getting up to, in her second novel, The Best of All Possible Worlds.

What’s remarkable about Lord’s oeuvre is that it’s near-unmatched: very few Caribbean writers, resident in the Caribbean, commit themselves to speculative fiction. Lord tells stories that are not only fascinating emotionally and anthropologically, but she’s doing it in a singular literary field.

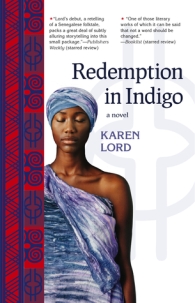

Lord’s first novel, Redemption in Indigo (Small Beer Press, 2010) was longlisted for the 2011 OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature. In its unpublished manuscript format, the novel won the 2008 Frank Collymore Literary Award. The Best of All Possible Worlds also received the Frank Collymore award, in 2009.

As with so much speculative fiction, the ambitions of Lord’s second novel are vast – and for the most part, they find confident footing. The story is narrated principally by Grace Delarua, a plucky biotechnician and resident of polycultural planet Cygnus Beta. Delarua is assigned to a social research expedition in service of the Sadiri, a proud, intellectually advanced race whose home territory has been obliterated. Represented by their chief councillor, Dllenahkh, the Sadiri seek out potential mates most similar to their own core temperament and physical appearance, on the many separate homesteads scattered throughout Cygnus Beta’s outposts and provinces.

Perhaps Redemption in Indigo bore more easily recognizable hallmarks of folkloric treatment (unsurprisingly, given that it’s a creative retelling of a Senegalese folk tale.) However, the avoidance of monoculturalism is gratifyingly strong in Lord’s second work. Cygnus Beta is described as “a galactic hinterland for pioneers and refugees,” and is populated with a diverse set of races, each with their own identifiable quirks and passions. Dllenahkh’s Sadirian measured equanimity finds a consistently pleasurable foil in Delarua’s Cygnian matter of factness and emotional volubility. The two give every indication, in the novel’s earliest stages, of being well-suited to the kind of romance that not only links two people, but solidifies tenuous bridges of cultural commingling.

This seems to be one of the central premises Lord works out in the novel. The universe’s various citizenries enact premeditated (and often brutal) acts of separatist violence against each other: witness Ain’s cavalier destruction of Sadiri, and the massive devastation this genocide left in its wake. Despite unfathomable loss and crippling exile, Lord prompts her central characters deeper into an understanding, and appreciation of, mutual dependency. Almost all of the novel’s players express strong attachments to concepts of home, kinship and domestic succor. Delarua says it herself, during an unexpected trip to her sister’s homestead:

“Blood is blood, you know? There’s too much shared history and too many cross-connecting bonds to ever totally extract yourself from that half-smothering, half-supporting, muddled net called family.”

It is perhaps slightly ironic, then, that Lord suggests that the connections we make, rather than those into which we are born, hold greatest sway. This isn’t a novel concept, but it’s engagingly transmitted through the writer’s exploration of psychic bonds, particularly the psionic linkages that Delarua and Dllenahkh test with each other. It’s not an especially groundbreaking way to talk about sensual or sexual intimacy in science fiction, but Lord recycles it well. Through these episodes, it feels like we see the potential couple most clearly, wherein they allow themselves to interface with vulnerability and trust. As Dllenahkh puts it, there can be a certain

“transcendence to bonding… feeling the bones, tendons and nerves of another being – not as a puppet master but like a dancer fitted to a partner, able to suggest a movement with a light press of silent, invisible communication.”

The novel’s greatest flaw is also one of its most affecting charms: it is both episodic in nature (as opposed to tackling one core issue head on in the plot), and it wants to say a great many things about a great many things. If the best of all possible worlds, according to the aphorism, is the one we’re living in now, then reading Lord grants us pathways to other places no greater than this Earth, but no less captivating.

This review first appeared in its entirety in the Trinidad Guardian‘s Sunday Arts Section on April 6th, 2014, entitled “Confident new Caribbean sci-fi novel.”

Published in 2010 by

Published in 2010 by

This review is proud to be part of Aarti’s A More Diverse Universe Reading Tour, a truly exciting event that seeks to showcase the broad spectrum of talent in speculative fiction written by authors of colour. A thrilling assortment of novels, short fiction collections and anthologies have been read and reviewed; for the full list of participants,

This review is proud to be part of Aarti’s A More Diverse Universe Reading Tour, a truly exciting event that seeks to showcase the broad spectrum of talent in speculative fiction written by authors of colour. A thrilling assortment of novels, short fiction collections and anthologies have been read and reviewed; for the full list of participants,