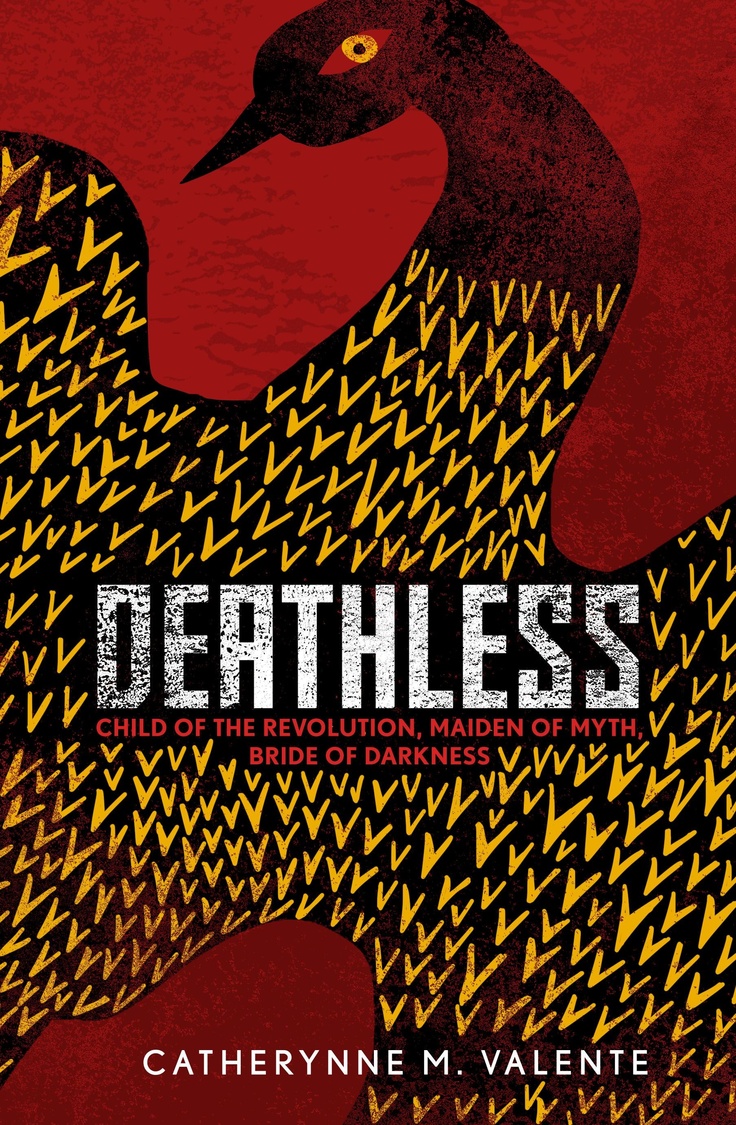

Published in 2011 by Tor Books.

There are various iterations of his accursed name, but in Slavic folklore, Koschei the Deathless augurs ill, particularly for the beautiful, chaste maidens he lures into his lap. As the ancient stories have it, Marya Morevna is his opposite: a steel-tempered warrior woman who brings the immortal, undying Tsar to heel, with chains and with stratagems. Russian children cut their teeth on these parables, and in their imaginations, such figures are hewn from the stardust of reality, fashioned in the space where our inherited stories possess, in their childhood telling, the greatest strength.

There are various iterations of his accursed name, but in Slavic folklore, Koschei the Deathless augurs ill, particularly for the beautiful, chaste maidens he lures into his lap. As the ancient stories have it, Marya Morevna is his opposite: a steel-tempered warrior woman who brings the immortal, undying Tsar to heel, with chains and with stratagems. Russian children cut their teeth on these parables, and in their imaginations, such figures are hewn from the stardust of reality, fashioned in the space where our inherited stories possess, in their childhood telling, the greatest strength.

Valente has claimed the tales of Koschei and Marya to enact the fable-ornate, revisionist tableaux of Deathless. Young Marya, her head filled with any number of strange, otherworldly things, lives in a house on Gorokhovaya Street, St. Petersburg, where she peers from her window out onto the street below. A husband, who begins his visitation to her as a bird, waits in her future. His arrival will confirm that she’s meant to step over the veil that shrouds the Other World from easy sight. It is a realm in which she, so unlike her sisters three, belongs. She cannot predict that her husband will be Koschei himself, cloaked in the raiment of a young man’s beauty. Though Marya has not bargained for Koschei’s hungry entreaty — that she follow him into the wide maw of uncertainty, far away from her home — she goes, making the bargain for ill, or good.

Deathless spans the Russian Soviet Union history of the 1920s through to the 1940s. The reader sees St. Petersburg become Petrograd, morphing into the Leningrad that endures the unspeakable grief, and human cost, claimed by the over two-year long Blockade. Marya is present, her consciousness superimposed over the multiply-tiered storylines of this Russia, and another: the undying lands of Buyan, Koschei’s kingdom where everything lives, even walls of responsive skin and fountains ceaselessly spurting arcs of blood. In this realm, the one to which Marya has been stolen away by her immortal lord, the human maiden blossoms into a hard-won womanhood, thrice-tested by the wicked tasks that Baba Yaga, Koschei’s demon sister, the Tsaritsa of Night, commands.

Those unfamiliar with Valente’s writing style will fall headfirst into the thicket of her prose, as adorned and intricate as ever it’s appeared — though perhaps considerably less breathless, less prone to swoops and sky-curlicues than it appears in the dizzyingly lush Palimpsest. The order of the narrative, through the intoxication of the language used to tell it, is stamped with the austerity of Soviet Russia. It’s a bureaucratic severity that seeps even into Koschei’s domain, as Baba Yaga herself reminds Marya, there’s always been a war, in and out of one girl’s reckoning with the war that shapes her, personally and politically.

Though it cleverly considers the landscapes surrounding an origin story (and the ways in which such terrain might be respectfully, usefully subverted), Deathless runs on fable. The structures of fairytale, principally the (re)occurrence of triumvirates, knit one Russia to the other, knit Marya’s one warrioress life with her domestic decisions in another realm. There is a necessary repetition to this that’s worth the occasional strain it puts, on the rate at which the braided stories canter along to their final destination.

Books like these are bold by default, because of the territory they excavate in order to achieve their own world: they cannot escape claims of cultural appropriation, nor should they. Deathless is a pulchritudinous, seductive fable that supplants emotional hierarchies of how Koschei, Marya, Baba Yaga and the Slavic folkloric contingent are perceived. It’s not written by someone to whom this folklore is native, and this will always be problematic for some of the indigenous recipients of the work, and the ways in which they come to bear on it.

I can’t claim to have my own compass points on cultural appropriation finitely fixed. It’s a dangerous thicket in which emotional and spiritual navigations can shift on the reassignation of a scrap of sacred ground. If you are of Russian lineage, if your ancestors lived, or else died, in Communist Leningrad, you may thrill to Valente’s fictive perceptions, or you may despise them. This, I think, remains your right.

Perhaps this makes my own task easier, less fraught with personal demarcations of inheritance, and resultant ownership. In every regard, Deathless is fiercely beautiful. It is assiduously researched, devotedly formatted, with attention lavished upon the stories, rituals and conquests of old.

What I love best — and there is no dearth of it throughout the worlds Valente helms in this moribund mythology — is the constant countermanding of what’s deemed “normal”. Weird love howls for triumphs, too, and in this territory, the surreal is as credible and palatable as the bread & buttered obvious. If you’re a feral adherent to that which is fanged, dark and plasma-patinated, then you’ll adore what passes between Koschei and Marya. Witness the scene in which he declares her unquestionably his, in the lull of a bitter quarrel, conducted in his smoky-pillared Chernosvyat:

“I will tell you why. Because you are a demon, like me. And you do not care very much if other girls have suffered, because you want only what you want. You will kill dogs, and hound old women in the forest, and betray any soul if it means having what you desire, and that makes you wicked, and that makes you a sinner, and that makes you my wife.”

If you’re wondering whether Marya and Koschei have lived out this scene through countless lives, don’t wonder: Valente makes it plain, using Baba Yaga, the novel’s most rollickingly well-managed auxiliary character, as mouthpiece. Auntie Yaga, not-uncruelly, tells Marya in plain terms:

“That’s how you get deathless, volchitsa. Walk the same tale over and over, until you wear a groove in the world, until even if you vanished, the tale would keep turning, keep playing, like a phonograph, and you’d have to get up again, even with a bullet through your eye, to play your part and say your lines.”

Death’s immutability is the novel’s garnet-studded spine, and the writer bestows gnawing, hungry pleasures for the reader who invests herself in unfurling its viscerally satisfying (albeit repetitive) revelations. If you come to the table famished, Deathless will ply you with loaves and wine, asking that you remember this story when you’re through, when you go fur-collared into glacial streets, to kiss your own Death on its grinning, strong mouth.

For a taste-test of Valente’s style: consider her short story “How to Become a Mars Overlord”, one of my Story Sunday posts. One of the principal characters in Valente’s Palimpsest is the answer to a Bookish Question I asked myself: When last did you catch an incontrovertible glance of yourself in fiction, and did you like the way you looked?

I read Palimpsest by Catherynne M. Valente in the last month of last year. Whenever I thought of reviewing it for Novel Niche, I felt that it wasn’t time. I felt, specifically, that there would be no way I could speak critically of a novel that had made me feel so much in love: in love with words and storytelling; in love with sexually-shared cityscapes, and in love with one of the four main characters of the story: November Aguilar, the beekeeper with a face that shows the places she has been in stark, difficult detail.

I read Palimpsest by Catherynne M. Valente in the last month of last year. Whenever I thought of reviewing it for Novel Niche, I felt that it wasn’t time. I felt, specifically, that there would be no way I could speak critically of a novel that had made me feel so much in love: in love with words and storytelling; in love with sexually-shared cityscapes, and in love with one of the four main characters of the story: November Aguilar, the beekeeper with a face that shows the places she has been in stark, difficult detail.