for D.A.W. (because we intermothered)

Who will take us in? This is what Glenda Moore was asking when she knocked on strangers’ doors for hours in late October 2012. Caught outside with her young sons in Staten Island, New York during Hurricane Sandy, she asked this when doors were opened, only to be closed in her face. (Later, some of the people who refused to help said they thought she was trying to burglarize their homes.) She asked this until she lost grip of her sons. Until the sea said, I will take them.

Who will take us in? This is what Glenda Moore was asking when she knocked on strangers’ doors for hours in late October 2012. Caught outside with her young sons in Staten Island, New York during Hurricane Sandy, she asked this when doors were opened, only to be closed in her face. (Later, some of the people who refused to help said they thought she was trying to burglarize their homes.) She asked this until she lost grip of her sons. Until the sea said, I will take them.

The bodies of Brandon, 2, and Connor, 4, were discovered nearby a few days later.

***

This is how marginalized mothers are unsheltered every day; this is why an arbor-anthology had to be built, and its name is Revolutionary Mothering: Love On The Front Lines (PM Press, 2016). The aim of this collection of communiqués, poems, essays, and visual art is to center mothers, who, like Moore, are locked out of “angel in the house” iconographies–i.e., primarily “radical mothers of color with a few marginalized (queer, trans, low income, single, and disabled) white mothers,” in the framing words of editors Alexis Pauline Gumbs, China Martens, and Mai’a Williams. And how do the editors define mothering? Panoramically. Enter this anthology knowing that there is a new spelling of the name: “m/other.” Spell it like “investing in each other’s existence,” as Loretta Ross does in the brilliant preface. Spell it like “less as a gendered identity and more a possible action, a technology of transformation,” as Gumbs does in her poetic, incandescent essay, “m/other ourselves: a Black queer feminist genealogy for radical mothering.” Spell it like “a primary front in this struggle {against a colonial, racist, hetero-patriarchal capitalism}, not as a biological function, but as a social practice,” as Cynthia Dewi Oka does in one of the book’s most electrifying entries, “Mothering as Revolutionary Praxis.”

“Revolutionary mothering” may be more redundant than oxymoronic, according to the biome of this book. However, Malkia A. Cyril reminds us in her incisive “Motherhood, Media, and Building a 21st-Century Movement,” the weaponized think-of-the-children has been used to undergird “a conservative vision of family” and the carceral state. Cyril asserts:

…empire is sustained, and mothers become one of the tools of its continuous resurrection.

But

just as mothers can become the ideological vehicles for hierarchy and dominance, they are uniquely positioned to lead both visionary and opposition strategies to it. With the right supports, mothers from underrepresented communities can help lead the way to new forms of governance, new approaches to the economy, and enlightenment of civil society grounded in fundamental human rights. In fact, they always have.

With blazing authority in “Forget Hallmark: Why Mother’s Day Is a Queer Black Left Feminist Thing,” Gumbs dismisses “the assumption that mothering is conservative or that conserving and nurturing the lives of Black children has ever had any validated place in the official American political spectrum.” (If it was so conservative, why have so many forces been arrayed against it?) Gumbs argues convincingly that Black motherHOOD is fundamentally insurgent; Black mothers, past and present, harbor futurity.

***

Witness the diversity of dispatches from the front lines: in Victoria Law’s “Doing It All…and Then Again with Child,” an organizer-mama writes letters to incarcerated women (many of them also mothers) that incorporate her daughter’s drawings–and travels to Chiapas, Mexico to hear Zapatista mothers talk about seamlessly integrating children into revolutionary struggle. Irene Lara invokes “Tlazolteotl, the Nahua sacred energy of birthing and regeneration” in the ceremony-limned “From the Four Directions: The Dreaming, Birthing, Healing Mother on Fire.” Mothers construct a theatre of testimony to resist genocide and extrajudicial killings in Arielle Julia Brown’s “Love Balm for My SpiritChild,” reminding me of the indefatigable Asociación Madres de Plaza de Mayo. In Lindsey Campbell’s “You Look Too Young to Be a Mom,” a chorus of young mas flip scripts that insist teen pregnancy is disaster unalloyed. tk karakashian tunchez megaphones “WE ARE WELFARE QUEENS AND WE AREN’T ASHAMED” in the manifesta, “Telling Our Truths to Live.” In “On My Childhood, El Centro del Raza, and Remembering,” Esteli Juarez re-members being raised by a father and other activists who occupied an abandoned school in Seattle, Washington for months, so that Chicanos, Mexicanos, and Latinos could have a public space to “gather, build community, access resources, [and] organize.”

The etymological root of “anthology” is “many flowers,” and Revolutionary Mothering is truly a fistful of spiky, necessary blooms. You need to be present for stories like these: Norma Angelica Marrun reflects on an undocumented childhood in the U.S. without her mother in “Why Don’t You Love Her?” In “Birthing My Goddess,” H. Bindy K. Kang is subjected to reproductive profiling and surveillance targeting South Asians in British Columbia. Terri Nilliasca reveals that the international adoption machine is built for white Westerners, and not balikbayan coming to the Philippines to adopt (“Night Terrors, Love, Brokenness, Race, Home & the Perils of the Adoption Industry: A Journey in Radical Family Creation”).

This book is riven with border lines–indeed, one of its conceits is lines, from “shorelines” to “between the lines”–and those lines matter. Border and bottom lines often mark what kind of mothering one has access to; Gumbs summons “immigrant nannies like my grandmother who mothered wealthy white kids in order to send money to Jamaica for my mother and her brothers who could not afford the privilege of her presence.” Cynthia Dewi Oka adds that “collectivizing caregiving in our communities is linked to dismantling a capitalist empire that abuses Third World women’s bodies as part of its infrastructure.” The children of marginalized mothers in the U.S., Loretta Ross makes clear, are primed to “become disposable cannon fodder for U.S. imperialism.”

There are some lines in the sand, uncrossable uncrossable. Gumbs calls out “neo-eugenicist” rhetoric and its relationship to “globalized ‘family planning’ agendas that have historically forced women in the Caribbean, Latin America, South Asia, and Africa to undergo sterilization in order to work for multinational corporations”; she also quotes officials who suggest that aborting Black fetuses in the U.S. will reduce crime and sterilizing women in “developing nations” will “prevent economically disruptive revolutions.” Oka punctures the population-bomb bogeyman embodied in “Black, indigenous, and Third World children…as perpetrators of environmental degradation.” In fact, mothering and radical homemaking are the imaginarium our moment needs, Oka insists–as she sketches a vision of the homes and habitats to come: “Perhaps the kind of home we need today is mobile, multiple, and underground.” The home as rhizome. A site of flux and disturbance, in the most generative sense. The home of the warning shot, to shoo away the State (see: Korryn Gaines). As an otherworldly realm of revolutionary eclipse and endarkenment: “Perhaps we need to become unavailable for state scrutiny so that we can experiment,” she muses, leaving us with a deepened “encumbrance upon each other while rejecting the extension of our dependence on state and capital.” Isn’t this kind of reliance and resiliency we will need, considering the demands of climate change? Is this what it means to mother in the Anthropocene?

***

Thankfully, this book doesn’t neglect to hold what is unresolved and difficult about mothering and being mothered. There’s pressure on people of color to craft reactive hagiographies about our mothers; while the impulse is understandable–don’t talk about your mother’s failures since the State is all too prepared to enumerate and criminalize them–stories like Rachel Broadwater’s “Brave Hearts” are refreshing. In it, Broadwater meditates on her disappointment with her own traumatized, imperfect mother. Mai’a Williams eschews the soft-focus sentimentality surrounding “mamahood” when she writes, “It’s a visceral sense that vulnerable, quivering life is breaking you and you have to let it. It’s not self-sacrifice. It may not even qualify as love. It isn’t sweet. It isn’t romantic.” This is beautifully and painfully illustrated in Vivian Chin’s essay, “Mothering,” which is mysterious, fraught with slippage, and haunted by damage not quite known. This is the anti-lullaby–this is rage-son, ankle bracelet, juvenile court, polliwogs not getting enough nutrients, you don’t help me with shit. Fabielle Georges’ “The Darkness” flickers with the radioactivity of colorism, lookism, and Black self-loathing. Claire Barrera talks about being short-fused due to chronic pain in “Step on a Crack: Parenting with Chronic Pain.”

***

If this anthology’s foremother is This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color–indeed, its initial title was This Bridge Called My Baby–then its sibling might be the zine movement. China Martens traces a brief history of “subculture media” that includes The Future Generation zine she started in 1990. Several zinesters are featured in Revolutionary Mothering, including Noemi Martinez of the zines, Making of a Chicana and Hermana, Resist. Martens explores how zines oiled her leap to blogs and “online snippets” especially suited to the time-strapped mom. Some of the anthology’s contributions (like Mamas of Color Rising’s “Collective Poem on Mothering”) read like raw, urgent telegraphs from mothers out of time–“time traveling is a necessity,” Martens says–and these seemingly rush-crafted pieces add to the anthology’s sense of welcome and immediacy.

***

Revolutionary Mothering is a dreambook. Place it on your bedstand and when you awaken, scribble your not-quite-daylight visions in the margins so your dreams will be in good company. With its protean take on mothering, expect to pick up a new book each time you open it. And while we’re dreaming, I would have loved more voices from mothers who embody the truth that “mother” is “older and more futuristic than the word ‘woman,’” as Gumbs wrote. Also invoked by Gumbs, I want more stories from the house mothers of ball culture themselves. Next time, then. I have gotten into the habit of collecting radical anthologies, and this one ranks among my favorites: I was rocked and healed and mothered by this open-armed anthology itself, and suspect it will go on to give birth to other anthologies, other worlds. Mothering got next.

If your potential was visible on your body, like a hologram of your future, you’d know what things to just give up on without trying . . . but then you’d never know that you change your hologram potential if you try.

—Rio, Katie Kaput’s nine-year-old son in “Three Thousand Words”

Those caregiving collectives? Those “phamilies, chosen and stronger than blood” tk karakashian tunchez speaks of? Yes, those. We have an amphibious city to build now, and Revolutionary Mothering offers so many blueprints, so much holographic potential. Let’s hold each other close, before the rising seas.

Almah LaVon is a poet errant and incogNegr@ who is often based in western Pennsylvania. More of her writing on books can be found in the forthcoming anthology, Solace: Writing, Refuge, and LGBTQ Women of Color.

Almah LaVon is a poet errant and incogNegr@ who is often based in western Pennsylvania. More of her writing on books can be found in the forthcoming anthology, Solace: Writing, Refuge, and LGBTQ Women of Color.

Shivanee’s postscript: It’s a tasselated, tapestried honour to have Almah’s critical work on Novel Niche! Many thanks to her, and to the editors and contributors of this formidable anthology, purchasable here.

Who will take us in?

Who will take us in?

Almah LaVon is a poet errant and incogNegr@ who is often based in western Pennsylvania. More of her writing on books can be found in the forthcoming anthology, Solace: Writing, Refuge, and LGBTQ Women of Color.

Almah LaVon is a poet errant and incogNegr@ who is often based in western Pennsylvania. More of her writing on books can be found in the forthcoming anthology, Solace: Writing, Refuge, and LGBTQ Women of Color.

Twenty four years have elapsed since the July 1990 attempted coup by the Jamaat al Muslimeen. Those who recollect the events of those six days in Trinidad and Tobago’s history do so with collective unease, channeling repressed fury and a kind of malaise that’s difficult to translate into common speech. This is what Monique Roffey’s fourth novel, House of Ashes (

Twenty four years have elapsed since the July 1990 attempted coup by the Jamaat al Muslimeen. Those who recollect the events of those six days in Trinidad and Tobago’s history do so with collective unease, channeling repressed fury and a kind of malaise that’s difficult to translate into common speech. This is what Monique Roffey’s fourth novel, House of Ashes (

Published by

Published by

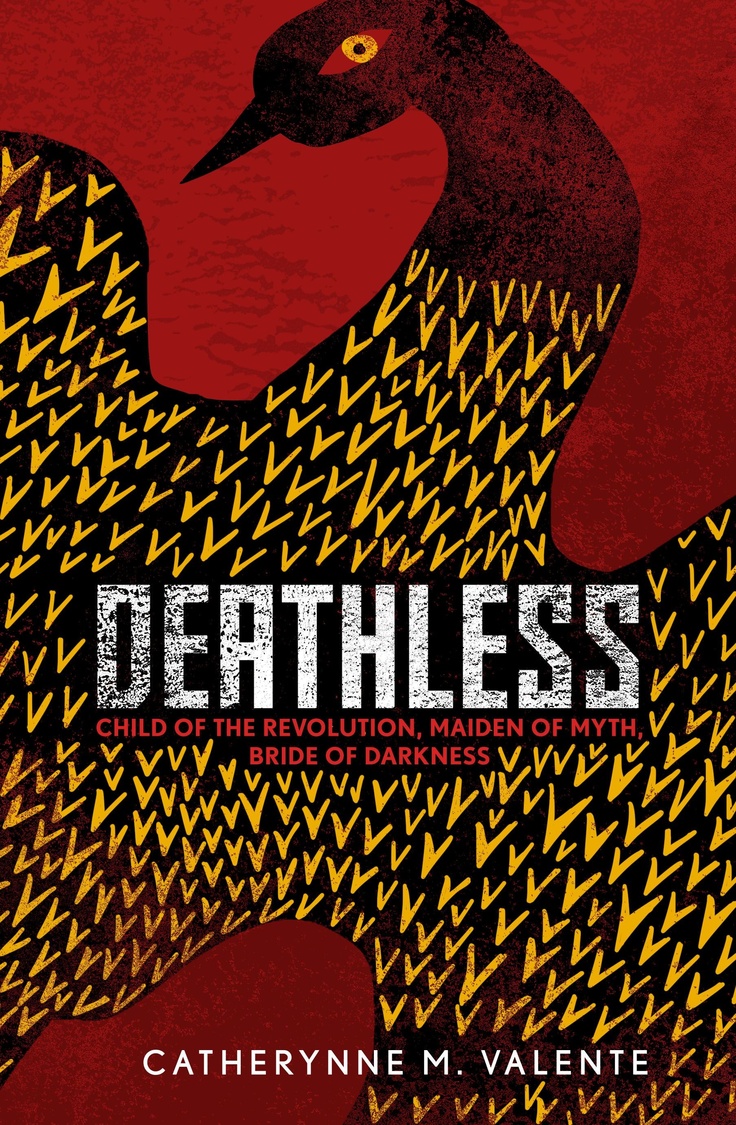

There are various iterations of his accursed name, but in Slavic folklore, Koschei the Deathless augurs ill, particularly for the beautiful, chaste maidens he lures into his lap. As the ancient stories have it, Marya Morevna is his opposite: a steel-tempered warrior woman who brings the immortal, undying Tsar to heel, with chains and with stratagems. Russian children cut their teeth on these parables, and in their imaginations, such figures are hewn from the stardust of reality, fashioned in the space where our inherited stories possess, in their childhood telling, the greatest strength.

There are various iterations of his accursed name, but in Slavic folklore, Koschei the Deathless augurs ill, particularly for the beautiful, chaste maidens he lures into his lap. As the ancient stories have it, Marya Morevna is his opposite: a steel-tempered warrior woman who brings the immortal, undying Tsar to heel, with chains and with stratagems. Russian children cut their teeth on these parables, and in their imaginations, such figures are hewn from the stardust of reality, fashioned in the space where our inherited stories possess, in their childhood telling, the greatest strength.

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (Junot Díaz) chronicles the lives of the titular character, Oscar Wao; his sister, Lola; his mother and grandfather. Oscar must deal with being overweight, a virgin and a Dominican still haunted by the ghost of the dictator, Rafael Trujillo. What lands this book here might be a strange one. It’s mainly because of the numerous accolades Díaz has received for it. Normally, I didn’t think people cared for the type of brash and vulgar storytelling employed in Oscar Wao. And honestly, it was right down my alley (writing-wise). When I saw that Díaz’s work could be accepted by the Pulitzer committee, I thought, “Why not mine?” As I said, strange reason. But it’s a damn unique and interesting book, nevertheless.

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (Junot Díaz) chronicles the lives of the titular character, Oscar Wao; his sister, Lola; his mother and grandfather. Oscar must deal with being overweight, a virgin and a Dominican still haunted by the ghost of the dictator, Rafael Trujillo. What lands this book here might be a strange one. It’s mainly because of the numerous accolades Díaz has received for it. Normally, I didn’t think people cared for the type of brash and vulgar storytelling employed in Oscar Wao. And honestly, it was right down my alley (writing-wise). When I saw that Díaz’s work could be accepted by the Pulitzer committee, I thought, “Why not mine?” As I said, strange reason. But it’s a damn unique and interesting book, nevertheless. The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (Jean-Dominique Bauby) is a memoir ‘written’ by a man who has locked-in syndrome. See, Mr. Bauby had been debilitated by a stroke, which rendered all but his left eye motionless. He blinked to the rhythm of a cautiously rearranged alphabet, and with a very, very patient nurse, this book exists. Just being able to read the book is a miracle, if you ask me. Within it contains the musings and memories of a man that thought he would be stuck in the deep, blue sea for the rest of his life. But now, from behind the steel cage of his diving bell, we can hear his voice. If this doesn’t readily reassure your belief in the power of the written word, I don’t know what will.

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (Jean-Dominique Bauby) is a memoir ‘written’ by a man who has locked-in syndrome. See, Mr. Bauby had been debilitated by a stroke, which rendered all but his left eye motionless. He blinked to the rhythm of a cautiously rearranged alphabet, and with a very, very patient nurse, this book exists. Just being able to read the book is a miracle, if you ask me. Within it contains the musings and memories of a man that thought he would be stuck in the deep, blue sea for the rest of his life. But now, from behind the steel cage of his diving bell, we can hear his voice. If this doesn’t readily reassure your belief in the power of the written word, I don’t know what will. Boy (Roald Dahl) is the first part of the autobiographical work by Dahl (the second part being Going Solo). It almost reads as an epistolary novel, as Dahl pastes clippings of letters, photographs and other family documents to relate his past in a whimsical manner. The chapters in Boy relate to a prank gone wrong at a candy shop, a grisly car accident and warming the toilet seats for the older boys at a school in Derbyshire. Despite its bursts of humour, it is the most serious book I’ve read from the author. Boy does not overshadow his fictional works, but it made me think: Life is remembered by how you tell it. If that makes sense.

Boy (Roald Dahl) is the first part of the autobiographical work by Dahl (the second part being Going Solo). It almost reads as an epistolary novel, as Dahl pastes clippings of letters, photographs and other family documents to relate his past in a whimsical manner. The chapters in Boy relate to a prank gone wrong at a candy shop, a grisly car accident and warming the toilet seats for the older boys at a school in Derbyshire. Despite its bursts of humour, it is the most serious book I’ve read from the author. Boy does not overshadow his fictional works, but it made me think: Life is remembered by how you tell it. If that makes sense. Miguel Street (V.S. Naipaul) is my second favourite Caribbean book (the first being Oscar Wao). My first encounter with the book, if I remember correctly, was a chapter featured in a primary school “Reading Book”. The chapter was about B. Wordsworth, a mysterious man who “felt like a poet but could never be one”. The story was strange and heartbreaking in its feeling of incompleteness. But there was nothing more to be said of B. Wordsworth, and the story was over. I think this was the first time I had read a truly sad ending to a story. The collection of stories in Miguel Street is well worth it, but I won’t forget that experience with B. Wordsworth.

Miguel Street (V.S. Naipaul) is my second favourite Caribbean book (the first being Oscar Wao). My first encounter with the book, if I remember correctly, was a chapter featured in a primary school “Reading Book”. The chapter was about B. Wordsworth, a mysterious man who “felt like a poet but could never be one”. The story was strange and heartbreaking in its feeling of incompleteness. But there was nothing more to be said of B. Wordsworth, and the story was over. I think this was the first time I had read a truly sad ending to a story. The collection of stories in Miguel Street is well worth it, but I won’t forget that experience with B. Wordsworth. The Sound and the Fury (William Faulkner) is the hardest book I’ve ever read, that I’ve ever finished (the hardest book I’ve never finished is The Scarlet Letter… trust me, fucking ridiculous!) Fury was my introduction to the much-beleaguered writing style known as stream-of-consciousness. In prose, anyway. Does Beat generation poetry count? It centers around the Compson family, sections devoted to various family members. The two that stood out the most to me were Benjy and Quentin. The non-linear narratives that rely on Benjy’s diminished mental capacity and Quentin’s disjointed and emotionally affected recollection of his family and his sister, Caddy, require multiple re-readings. I remember being on campus, busily dissecting the book during Biology lectures. It was my first experience with frustration that somehow felt rewarding simultaneously. Once you are willing to decipher it, it’s worth it.

The Sound and the Fury (William Faulkner) is the hardest book I’ve ever read, that I’ve ever finished (the hardest book I’ve never finished is The Scarlet Letter… trust me, fucking ridiculous!) Fury was my introduction to the much-beleaguered writing style known as stream-of-consciousness. In prose, anyway. Does Beat generation poetry count? It centers around the Compson family, sections devoted to various family members. The two that stood out the most to me were Benjy and Quentin. The non-linear narratives that rely on Benjy’s diminished mental capacity and Quentin’s disjointed and emotionally affected recollection of his family and his sister, Caddy, require multiple re-readings. I remember being on campus, busily dissecting the book during Biology lectures. It was my first experience with frustration that somehow felt rewarding simultaneously. Once you are willing to decipher it, it’s worth it. Disgrace (J.M. Coetzee) was a novel I received for free at a writing workshop when I was twenty. We were given a week to read the book for an upcoming book-club type discussion of character and theme. The story itself concerns David Lurie, a college professor fired for misconduct, who loses most of his reputation and integrity in the process. Yes, it is as depressing as it sounds. But there was one thing that stood out for me as I read this book: the present tense. I had never given it much thought before that. The present tense is quite effective once used properly. Not necessarily to build suspense or (no pun intended) tension or anything, but just to hold the reader in that moment of disarray and imminent disarray. I’ve been trying to re-create that ever since.

Disgrace (J.M. Coetzee) was a novel I received for free at a writing workshop when I was twenty. We were given a week to read the book for an upcoming book-club type discussion of character and theme. The story itself concerns David Lurie, a college professor fired for misconduct, who loses most of his reputation and integrity in the process. Yes, it is as depressing as it sounds. But there was one thing that stood out for me as I read this book: the present tense. I had never given it much thought before that. The present tense is quite effective once used properly. Not necessarily to build suspense or (no pun intended) tension or anything, but just to hold the reader in that moment of disarray and imminent disarray. I’ve been trying to re-create that ever since. Middlesex (Jeffrey Eugenides), to me, is the paragon of a bildungsroman (a coming-of-age tale), especially one that involves identity (most of them do, though, don’t they?) It’s a thick book, but that’s because it goes into so much detail with our protagonist, Cal, and his family’s migration from Asia Minor. The hook? Call is intersexed, afflicted with a genetic condition known as 5-ARD. The males are often mistaken for females all the way up to puberty, and are raised as such. The question isn’t about how this can be fixed, but: should it be fixed? Now, Eugenides’ style is verbose, be warned. But from the two books I’ve by him, it’s fitting and beautiful. When it comes to the dense, thorny theme of identity, I don’t think there could be enough words.

Middlesex (Jeffrey Eugenides), to me, is the paragon of a bildungsroman (a coming-of-age tale), especially one that involves identity (most of them do, though, don’t they?) It’s a thick book, but that’s because it goes into so much detail with our protagonist, Cal, and his family’s migration from Asia Minor. The hook? Call is intersexed, afflicted with a genetic condition known as 5-ARD. The males are often mistaken for females all the way up to puberty, and are raised as such. The question isn’t about how this can be fixed, but: should it be fixed? Now, Eugenides’ style is verbose, be warned. But from the two books I’ve by him, it’s fitting and beautiful. When it comes to the dense, thorny theme of identity, I don’t think there could be enough words. The Virgin Suicides (Jeffrey Eugenides) is a shorter book than Eugenides’ Middlesex, but it’s no less loaded with purple prose. The story is told by a group of men as they recall and muse upon the sudden suicides of the reclusive Lisbon girls in their neighbourhood. Their actual interaction with them was minimal, so they resort to filling in the blanks with theories of domestic horror. However, The Virgin Suicides never wanders into any gruesome vision. It is probably the least angsty book about suicide I’ve read. Instead, the story focuses on teenage whimsy and puppy love in light of what has happened, as if the girls themselves were pixies perched on mushrooms, or some other magical beings. The book feels like magical realism, though entirely grounded in drama and disillusioned romance. Why this book is here is because it holds that intangible quality that separates melancholy from melodrama. It remains my key to written emotion.

The Virgin Suicides (Jeffrey Eugenides) is a shorter book than Eugenides’ Middlesex, but it’s no less loaded with purple prose. The story is told by a group of men as they recall and muse upon the sudden suicides of the reclusive Lisbon girls in their neighbourhood. Their actual interaction with them was minimal, so they resort to filling in the blanks with theories of domestic horror. However, The Virgin Suicides never wanders into any gruesome vision. It is probably the least angsty book about suicide I’ve read. Instead, the story focuses on teenage whimsy and puppy love in light of what has happened, as if the girls themselves were pixies perched on mushrooms, or some other magical beings. The book feels like magical realism, though entirely grounded in drama and disillusioned romance. Why this book is here is because it holds that intangible quality that separates melancholy from melodrama. It remains my key to written emotion. The Road (Cormac McCarthy) concerns a father and son’s journey across a wasteland, the near-shell of a once-verdant world. The technique employed by McCarthy to show the stark emptiness of this situation? The abandonment of punctuation. While I had experienced the fiddlings of grammatical structure before, like with ee cummings, I never reckoned any operative utilisation of it with a novel. Like The Call of the Wild, The Road is written with a complex simplicity (you’ve probably figured out that I’ve an inclination for this odd oxymoron). It describes desolation in brief whispers. Hopelessness in dying breaths. No need for abundance of any sort here.

The Road (Cormac McCarthy) concerns a father and son’s journey across a wasteland, the near-shell of a once-verdant world. The technique employed by McCarthy to show the stark emptiness of this situation? The abandonment of punctuation. While I had experienced the fiddlings of grammatical structure before, like with ee cummings, I never reckoned any operative utilisation of it with a novel. Like The Call of the Wild, The Road is written with a complex simplicity (you’ve probably figured out that I’ve an inclination for this odd oxymoron). It describes desolation in brief whispers. Hopelessness in dying breaths. No need for abundance of any sort here. The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time (Mark Haddon) concerns Christopher Boone as he plays detective to discover who stabbed his neighbour’s dog, and ultimately uncovers the dark secrets kept by his family. Christopher, however, lives with an autistic spectrum condition and experiences great difficulty accepting the hard realities of his findings. The book is told from first person and is much easier to read than Benjy’s portion in The Sound and the Fury and is more on par with the emotional journey in Flowers for Algernon, though it does require patience when Christopher’s OCD steps in and prevents the plot from advancing. This is all done for effect, however, and works most of the time. This book lands a place on this list for its ability to integrate Christopher’s medical condition into the narrative, not as a gimmick or technique, but to show how different people process different situations. How I may have reacted to Christopher’s findings might have been much different, but this is his story. And everyone should have a story, shouldn’t they?

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time (Mark Haddon) concerns Christopher Boone as he plays detective to discover who stabbed his neighbour’s dog, and ultimately uncovers the dark secrets kept by his family. Christopher, however, lives with an autistic spectrum condition and experiences great difficulty accepting the hard realities of his findings. The book is told from first person and is much easier to read than Benjy’s portion in The Sound and the Fury and is more on par with the emotional journey in Flowers for Algernon, though it does require patience when Christopher’s OCD steps in and prevents the plot from advancing. This is all done for effect, however, and works most of the time. This book lands a place on this list for its ability to integrate Christopher’s medical condition into the narrative, not as a gimmick or technique, but to show how different people process different situations. How I may have reacted to Christopher’s findings might have been much different, but this is his story. And everyone should have a story, shouldn’t they?

The Pleasures of the Damned (Charles Bukowski) is a collection of poems by, well, Charles Bukowski. In my review for this book, I said that Bukowski is overbearingly honest in most of his poetry. He creates dystopia without apocalypse. The ordinary degenerate. There’s nothing else to it, since basically he was a degenerate. The collection, however, made me view poetry in a different light when I first discovered Bukowski at fifteen. Poetry didn’t have to be embellished or written with finely curled letters. It could be simple and ugly. Not even well-articulated hatred, like Sylvia Plath. Just raw, pithy imagery about toughness, like a one-eyed cat, a tough motherfucker, chasing blind mice.

The Pleasures of the Damned (Charles Bukowski) is a collection of poems by, well, Charles Bukowski. In my review for this book, I said that Bukowski is overbearingly honest in most of his poetry. He creates dystopia without apocalypse. The ordinary degenerate. There’s nothing else to it, since basically he was a degenerate. The collection, however, made me view poetry in a different light when I first discovered Bukowski at fifteen. Poetry didn’t have to be embellished or written with finely curled letters. It could be simple and ugly. Not even well-articulated hatred, like Sylvia Plath. Just raw, pithy imagery about toughness, like a one-eyed cat, a tough motherfucker, chasing blind mice. Slaughterhouse-Five (Kurt Vonnegut) concerns Billy Pilgrim, who becomes “unstuck in time”. After being abducted by a strange group of aliens, Billy finds that he can see his entire life (and even past his death, until the end of the universe itself). I read this in university and it changed my perspective on how science fiction could be written. Vonnegut, to me, seems to write with an extraterrestrial readership in mind. There is a certain humour in the simplicity we take for granted. Vonnegut captured that here. It is something I hope to also.

Slaughterhouse-Five (Kurt Vonnegut) concerns Billy Pilgrim, who becomes “unstuck in time”. After being abducted by a strange group of aliens, Billy finds that he can see his entire life (and even past his death, until the end of the universe itself). I read this in university and it changed my perspective on how science fiction could be written. Vonnegut, to me, seems to write with an extraterrestrial readership in mind. There is a certain humour in the simplicity we take for granted. Vonnegut captured that here. It is something I hope to also. The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian (Sherman Alexie) concerns Arnold Spirit, as he grows up in the ‘rez’ (Indian reservation), surrounded by disillusioned, drunk and temperamental Native Americans. This is the quintessential young-adult book, yes, complete with bullying, falling in love and illustrations. And it is quite remarkable. Young-adult authors engineer their books to extract an emotional catharsis, I believe. Finding humour in degradation. And the great fear that settles when one is told of their own home, “This place will kill you.” Living in a crime-ridden country, I can relate. Also, who knew comic strip cartoons could go so well with prose?

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian (Sherman Alexie) concerns Arnold Spirit, as he grows up in the ‘rez’ (Indian reservation), surrounded by disillusioned, drunk and temperamental Native Americans. This is the quintessential young-adult book, yes, complete with bullying, falling in love and illustrations. And it is quite remarkable. Young-adult authors engineer their books to extract an emotional catharsis, I believe. Finding humour in degradation. And the great fear that settles when one is told of their own home, “This place will kill you.” Living in a crime-ridden country, I can relate. Also, who knew comic strip cartoons could go so well with prose? The Catcher in the Rye (J.D. Salinger) is a book we all know, or should know. It is a polarizing book, not for its content so much, but because it has been read by some of the most irritating people. Holden Caulfield has been kicked out of Pencey Prep and wanders around New York City for a few days before returning home. He also wears a red hunting cap. That’s it. That’s the book. And I’ve read it, no exaggeration, about ten times. I read this when I was fourteen after I borrowed it from my school library. Didn’t know anything about it when I did, but damn, it was hard to do my homework the night I started it. I don’t love Holden. I don’t even like him. But I realise: I don’t have to. It helps, yes, to feel something for a narrator. But I realised that they don’t always have to be affable. Just intriguing, as character is the greatest tool we have to elevating plot.

The Catcher in the Rye (J.D. Salinger) is a book we all know, or should know. It is a polarizing book, not for its content so much, but because it has been read by some of the most irritating people. Holden Caulfield has been kicked out of Pencey Prep and wanders around New York City for a few days before returning home. He also wears a red hunting cap. That’s it. That’s the book. And I’ve read it, no exaggeration, about ten times. I read this when I was fourteen after I borrowed it from my school library. Didn’t know anything about it when I did, but damn, it was hard to do my homework the night I started it. I don’t love Holden. I don’t even like him. But I realise: I don’t have to. It helps, yes, to feel something for a narrator. But I realised that they don’t always have to be affable. Just intriguing, as character is the greatest tool we have to elevating plot. Johnny Got His Gun (Dalton Trumbo) is similar to another book I have on this list, The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, though they are both here for different reasons. Joe Bonham awakens in a hospital and eventually deduces that he is basically a living torso. Yes, his face is gone and his appendages have all been blown off by an artillery shell. He’s a prisoner in his own body. It is a poignant and extremely depressing novel. It is here because of its attention to sensory detail and use of flashback during the recall of Joe’s life and family. It also shows the influence the written word can have against a behemoth such as World War I.

Johnny Got His Gun (Dalton Trumbo) is similar to another book I have on this list, The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, though they are both here for different reasons. Joe Bonham awakens in a hospital and eventually deduces that he is basically a living torso. Yes, his face is gone and his appendages have all been blown off by an artillery shell. He’s a prisoner in his own body. It is a poignant and extremely depressing novel. It is here because of its attention to sensory detail and use of flashback during the recall of Joe’s life and family. It also shows the influence the written word can have against a behemoth such as World War I. The Gunslinger (Stephen King) is the first book of the Dark Tower series, the magnum opus of King’s career, and I’ve put it here to represent both itself and the series. Though I’ve only read up to its fourth installment, the series is a detailed and expansive work that treads through the wasteland of a world that can only be described as where “the rest of the world has moved on”. Characters from previous novels make appearances, affecting the plot and reinforcing the idea that all King’s work is set in one universe. A haunting western setting along with deliberate anachronisms showed me that there really is no boundary to the worlds you can conjure up. Everything is acceptable, once done calculatingly and professionally.

The Gunslinger (Stephen King) is the first book of the Dark Tower series, the magnum opus of King’s career, and I’ve put it here to represent both itself and the series. Though I’ve only read up to its fourth installment, the series is a detailed and expansive work that treads through the wasteland of a world that can only be described as where “the rest of the world has moved on”. Characters from previous novels make appearances, affecting the plot and reinforcing the idea that all King’s work is set in one universe. A haunting western setting along with deliberate anachronisms showed me that there really is no boundary to the worlds you can conjure up. Everything is acceptable, once done calculatingly and professionally. Everything’s Eventual (Stephen King) is a short story collection, of which I wish to discuss only the titular story. “Everything’s Eventual” concerns Dinky Earnshaw, who has the ability to construct symbols that elicit strong suicidal feelings for those who view them. Dinky doesn’t understand his ability, and doesn’t use it until he is convinced to do it to rid evildoers in his city. I was thirteen when I read this, and I had never even imagined that such a Jedi-like mind trick could be taken seriously out of a Star Wars setting. King made it work, however. From an early age, because of this story, I realised how limitless writing really was. Sorcery could exist in suburbia, and that was fine.

Everything’s Eventual (Stephen King) is a short story collection, of which I wish to discuss only the titular story. “Everything’s Eventual” concerns Dinky Earnshaw, who has the ability to construct symbols that elicit strong suicidal feelings for those who view them. Dinky doesn’t understand his ability, and doesn’t use it until he is convinced to do it to rid evildoers in his city. I was thirteen when I read this, and I had never even imagined that such a Jedi-like mind trick could be taken seriously out of a Star Wars setting. King made it work, however. From an early age, because of this story, I realised how limitless writing really was. Sorcery could exist in suburbia, and that was fine. Flowers for Algernon (Daniel Keyes) is an epistolary novel (and I actually didn’t know what that meant until I read it) about Charlie Gordon, a mentally challenged janitor whose rapidly increasing intellect affects his life and those around him. As it is an epistolary novel, the story takes place in entries from Charlie’s journal. The result is quite effective, as it shows both Charlie’s own changes in his thought processes, and clarity of events in hindsight. I came across this in a second hand book kiosk while I was in high school, and I actually had no idea at the time that books could be structured that way successfully.

Flowers for Algernon (Daniel Keyes) is an epistolary novel (and I actually didn’t know what that meant until I read it) about Charlie Gordon, a mentally challenged janitor whose rapidly increasing intellect affects his life and those around him. As it is an epistolary novel, the story takes place in entries from Charlie’s journal. The result is quite effective, as it shows both Charlie’s own changes in his thought processes, and clarity of events in hindsight. I came across this in a second hand book kiosk while I was in high school, and I actually had no idea at the time that books could be structured that way successfully. The Chrysalids (John Wyndham) is a book that most high school students around my time might have done for their O’ Level Literature class. Though I didn’t study Literature, I read the book anyway. I was probably thirteen at the time. The story concerns David, one of a group of telepathic children whom live in Labrador. The people of Labrador believe that any deviation of the human anatomy (or ability) must be banished to the “Fringes”. It’s one of those classical allegory stories that youngsters are told to read, like Animal Farm. And while Animal Farm carried a strong message, it didn’t affect me as much as Chrysalids’. It carries one that is central to literature itself: never stop analysing everything.

The Chrysalids (John Wyndham) is a book that most high school students around my time might have done for their O’ Level Literature class. Though I didn’t study Literature, I read the book anyway. I was probably thirteen at the time. The story concerns David, one of a group of telepathic children whom live in Labrador. The people of Labrador believe that any deviation of the human anatomy (or ability) must be banished to the “Fringes”. It’s one of those classical allegory stories that youngsters are told to read, like Animal Farm. And while Animal Farm carried a strong message, it didn’t affect me as much as Chrysalids’. It carries one that is central to literature itself: never stop analysing everything. The Call of the Wild (Jack London) concerns Buck, a domesticated dog that has been sold to become an Alaskan sled dog. The language is straightforward yet descriptive and the primal themes retain power in their simplicity, so when I read this at a very young age, it hit hard. It’s probably one of the most effective books I’ve read. It doesn’t miss a beat and the theme of “returning to nature” will always be relevant to literature, to society, to any persona one may hold. We all must be animals when the time comes.

The Call of the Wild (Jack London) concerns Buck, a domesticated dog that has been sold to become an Alaskan sled dog. The language is straightforward yet descriptive and the primal themes retain power in their simplicity, so when I read this at a very young age, it hit hard. It’s probably one of the most effective books I’ve read. It doesn’t miss a beat and the theme of “returning to nature” will always be relevant to literature, to society, to any persona one may hold. We all must be animals when the time comes.