How better to stun Babylon than with serpents?

Vengeance is one thing, and justice another. Which of these two snakes would bite harder, poison faster? Shara McCallum‘s “The Madwoman as Rasta Medusa” does not leave us guessing. Announcing the arrival of a serpentine-coiled agent of Armagiddeon, the poem hisses, “Yu think, all these years gone, / and I-woman a come here fi revenge? / But yu wrong. Again is so yu wrong.”

In the space where all blood debts must be paid in sanguinary tithes, this mad rasta medusa comes with a ready salver, promising no Perseus will take her head. In this mythos, one gleefully suspects Perseus is a trifling youthman who can’t even cock his own gun, far less trouble the scaled tail of the I-woman.

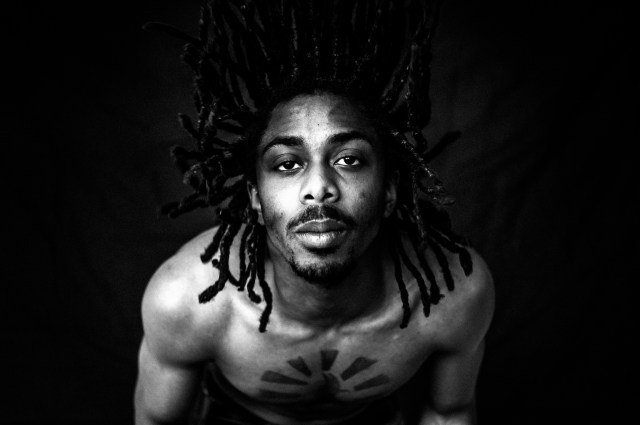

With all the unaplogetic, swaggering braggadocio you might find in a Midnight Robber speech, Rasta Medusa enters, her own body a terrible, calcifying witness. Not terrible as in, “I caught a terrible cold and have to miss work.” Terrible as in, “The face of the creature shone, sovereign and terrible, and all men quaked.”

Witness the Rasta Medusa’s biological weaponry: “This face, etch with wretchedness, / these dreads, writhing and hissing / misery”. How triumphantly precise is this mapping of the female-identified body as its inbuilt defense, its native artillery, its original vessel, vanguard and future tomb?

We all know the I-woman. We have all beheld her in our dreams, our fantasies, our Sunday morning marketplaces and Saturday night sweatdown sessions. Maybe she can flex on her head. Maybe she can cure the sick with cerassee and senna. Maybe she is the leveller of men, the liberator of women, the herald of the right and ready now. Instead of the bat signal, how can we call her when we have terrible need?

Read “The Madwoman as Rasta Medusa” here.

Shara McCallum’s Madwoman is the winner of the 2018 OCM Bocas Poetry Prize.

This is the fifteenth installment of Puncheon and Vetiver, a Caribbean Poetry Codex created to address vacancies of attention, focus and close reading for/of work written by living Caribbean poets, resident in the region and diaspora. During April, which is recognized as ‘National’ Poetry Month, each installment will dialogue with a single Caribbean poem, available to read online. NaPoWriMo encourages the writing of a poem for each day of April. In answering, parallel discourse, Puncheon and Vetiver seeks to honour the verse we Caribbean people make, to herald its visibility, to read our poems, and read them, and say ‘more’.

This is the fifteenth installment of Puncheon and Vetiver, a Caribbean Poetry Codex created to address vacancies of attention, focus and close reading for/of work written by living Caribbean poets, resident in the region and diaspora. During April, which is recognized as ‘National’ Poetry Month, each installment will dialogue with a single Caribbean poem, available to read online. NaPoWriMo encourages the writing of a poem for each day of April. In answering, parallel discourse, Puncheon and Vetiver seeks to honour the verse we Caribbean people make, to herald its visibility, to read our poems, and read them, and say ‘more’.