Inspired by Buried in Print‘s indepth and illuminating story-by-story analysis of Alice Munro’s collections, I’ve decided to read Munro’s The Love of a Good Woman (1998, McClelland & Stewart) in same spirit of individual story appreciation, delight and scrutiny. I’m beginning with the first (and titular) story of the collection, “The Love of a Good Woman”.

This is how my introduction to the world of Alice Munro’s writing begins – with a drowning. A man, an optometrist named D.M. Willens, loses his life to the Peregrine River in 1951. The reader learns this through the object that opens “The Love of a Good Woman”: a red box of optometrist’s tools, which contains, among other things, an ophthalmoscope.

This is how my introduction to the world of Alice Munro’s writing begins – with a drowning. A man, an optometrist named D.M. Willens, loses his life to the Peregrine River in 1951. The reader learns this through the object that opens “The Love of a Good Woman”: a red box of optometrist’s tools, which contains, among other things, an ophthalmoscope.

Munro wields this object with dual stylistic purpose – in her deft hands, it is both a promontory and a point of multiple divergences. We are allowed to trace the history of the ophthalmoscope backwards through time, to the quiet, sturdy town of Walley (in whose museum of quaint domesticities the device is housed). We get to breathe Walley in; we’re allowed to take its unremarkable temperature. We peer into the lives of three boys who, while surveying their riverbank domain, happen upon Willens’ car, buried in pond mud like a light blue absurdity. We stay with each lad awhile, privy to the small and considerable distresses and merriments of their lives, until they tell Walley that the optometrist has drowned.

Time passes. The boys grow up, and Willens’ death becomes part of Walley’s remembered history. We meet and spend time with a woman who is admonished by her mother for throwing herself towards sainthood. She’s called Enid, and she is tending to Mrs. Quinn, who is dying of a rare illness whose symptoms are both grotesque and medically fascinating. On her deathbed, trapped in the resentment of her prolonged, focused misery, Mrs. Quinn contains secrets. When she shares one of them with Enid, certain things once held as true begin to fray, threatening to dredge up old drownings with new, sharp interrogations.

Majestic flourishes of language don’t typify how Munro tells this story. It’s more like the language is majestically suited to a series of nimble purposes. She captures the impetuous shock (and its robust aftermath) that goosepimples the skin of the boys, who dive into the Peregrine:

“So they would jump into the water and feel the cold hit them like ice daggers. Ice daggers shooting up behind their eyes and jabbing the tops of their skulls from the inside. Then they would move their arms and legs a few times and haul themselves out, quaking and letting their teeth rattle; they would push their numb limbs into their clothes and feel the painful recapture of their bodies by their startled blood and the relief of making their brag true.”

Alice Munro, it turns out, is like this stealth rogue who shivs you with at least ten difficult-to-name emotions when you weren’t even expecting to feel your heartbeat race. A full repertoire of individual sorrows and contemplations, plus the collective memory of a town that’s no quieter than its ghosts are silent and well-mannered, resides in this telling. There’s the consideration of all these lives from multiple, age-tiered perspectives. Munro feeds us slices of devil-may-care, boyish bravado, and injects us with doses of a nurse’s calm equanimity; she does both while winning our absolute belief that she keenly sees each person we meet in her pages.

The writer shows us that the boys aren’t just brash; they’re also beset by varying degrees of domestic trauma, over which they may or may not feel duly traumatized. She peels away the nurse’s graceful routine by night, summoning up for her a host of sleepless hours, and private agonies over choosing what’s right, what’s useful, what future might be hers based on speaking, or else saying nothing at all.

“The Love of a Good Woman” ends as so much of it is conducted, with quietness blanketing one’s orbit, while the world continues its indifferent geographical circuitry. There is no easy way to know how Enid will fare, at the story’s close – what is clear is that she won’t end. The ambit of her drama will continue to lope, and loop; one feels intensely that her life is happening to her even now, while dinners are being made in the real world, while blog posts are being written. She is the real world, Alice Munro tells us, and her life is just about as unremarkable and miraculous as any of ours, whether we are helping someone breathe, or watching them falter, seeing them sink with other secrets to the lake’s still bed.

Here’s Buried in Print’s incisive analysis of “The Love of a Good Woman”. Next up, I’ll be discussing the collection’s second story, “Jakarta”.

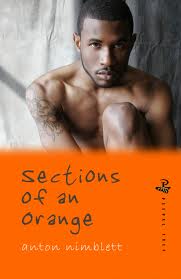

Published in 2011 by

Published in 2011 by  Published in 2006 by

Published in 2006 by

Duane Allicock hails from the island of Trinidad and lives for reading, cycling and running; in that order. When not pursuing any of these passions, he prefers to immerse himself in listening to music, or the silence of the Mount Saint Benedict monastery, pondering on life’s humorous ironies.

Duane Allicock hails from the island of Trinidad and lives for reading, cycling and running; in that order. When not pursuing any of these passions, he prefers to immerse himself in listening to music, or the silence of the Mount Saint Benedict monastery, pondering on life’s humorous ironies. [This is a review of an erotica collection. It should not be read by anyone who is too young to read erotica.]

[This is a review of an erotica collection. It should not be read by anyone who is too young to read erotica.] You can purchase And Then Her Mouth

You can purchase And Then Her Mouth  “God, that’s sexy as hell.”

“God, that’s sexy as hell.”

“I get her arms in front and see words written on them. It freaks me out. But it’s just words. ‘Stop looking,’ she says. ‘Stop reading.’ Lord Harry the Judge. I lay back in my seat and I just ask, ‘This is stupid. You couldn’t find no paper?’ She shakes her head, ‘I left my notebook.’ I open the golf and show her the roller paper, like a small notepad. ‘I didn’t think of that’ she say with her voice going all Yankee now. And then she crying like I hit her or something. She sit on her hands the whole drive back. Keep her arms tight by her side. Tonight, I think, I going kiss those arms. I going lick every word if she let me.”

“I get her arms in front and see words written on them. It freaks me out. But it’s just words. ‘Stop looking,’ she says. ‘Stop reading.’ Lord Harry the Judge. I lay back in my seat and I just ask, ‘This is stupid. You couldn’t find no paper?’ She shakes her head, ‘I left my notebook.’ I open the golf and show her the roller paper, like a small notepad. ‘I didn’t think of that’ she say with her voice going all Yankee now. And then she crying like I hit her or something. She sit on her hands the whole drive back. Keep her arms tight by her side. Tonight, I think, I going kiss those arms. I going lick every word if she let me.”